Reality (a Manual of Pragmatism) - (ENG)

It seems there's something out there. This apparently innocent statement can become quite problematic. And it's perhaps one of the most necessary thoughts for understanding how we truly relate to reality.

Trying to understand it by living it in our own skin is the best we can do, but even then we won't be able to really understand it. Why? Because reality, the world out there, is infinitely complex, and our human sensors only monitor a few 'parameters' that are projected at human scale (which are the senses). We oversimplify it.

The big lie our brain tells us

In fact, our natural tendency is to think that we do have direct access to the world and that we understand what's happening around. Bzzt. Wrong. We always speak as if what we see was complete reality, when in fact we only have access to how things appear to us. But this is just a lie our brain tells us. We don't understand anything at all, but recognizing this would be paralyzing for us and for all the mammalian species that came before us.¹

Let's try this: think about the last time someone explained to you what a place you didn't know was like. Did you imagine it exactly as it was? Probably not.

Then we arrive at the real problem... if our perception deceives us and other people's explanations also fail, what's happening?

The problem here isn't just the inaccessible complexity of reality but also that the tools we use to understand it are insufficient. It may seem like an excessively analytical view, but when it comes to understanding reality, our main tool is largely a spoke in the wheels: I'm talking about the deception of words.

The trap of words

In summary, words have two major problems:

- The precision problem: there's rarely a word that says exactly what you want to say.

- The interpretation problem: the other person understands something different from what you meant to say.²

If our goal is to understand things deeply, the worst thing we can do is to quickly look for "comfortable" narratives that explain everything elegantly. Much less assume abstract "ideas" that pretend to summarize a thousand things in a single abstract concept.³

When I say "narratives", I mean, for example, a text or a person who explains to us what a town or a movie is like. Words (natural language) are useful for quick communication between humans (they make us feel intensely), but they don't scale well if what we want is to describe reality exhaustively. We would say that words are useful for communicating with each other... as long as we don't want to say anything too precise.⁴

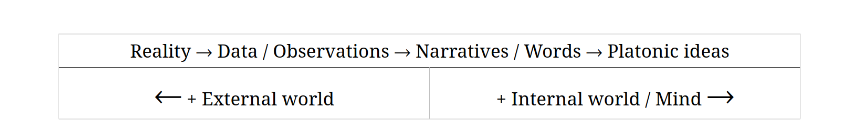

Data, on the other hand, is bad for quickly communicating day-to-day matters but scales well if you have a lot of it. Here I'm talking about data in a broad sense: measurements or numbers that are extracted from nature and that can be combined to do analysis and better understand reality.

In practice, data would be closer to this thing out there⁵ that is reality, and words would be closer to the human mind.

This explains why people who are good at communicating are good with words, but people who need to know things deeply have to deal with data. Humans operate better with words, but words are extremely deceptive.

The solution

Not everything is lost apart from collecting data about things and refusing to assume easy narratives. There's actually a shortcut to accessing reality. It may seem simple, but, as I said at the beginning, the best way to know reality is to live it directly, to be exposed to it firsthand. Humans are excellent at capturing information from the real world firsthand.

Even though we're later unable to explain or process the experiences, by living situations firsthand we learn much, much more than we're even aware of. Do you want to understand a culture? Live it. Want to know a person? Chat with them face-to-face. Want to learn a new skill? Practice it.

In short: it seems there's something out there. If you want to understand it, the best approach is to live out there, followed by analyzing its data and finally having it explained to you with words. Life, analysis, narrative.