The other (or Love in the Age of AI Girlfriends)

It’s easy to feel that other people are so complex that we’ll never fully understand them.

I had originally drafted a more philosophical piece about Levinas’ thought in 2025, but a couple of recent articles made me scrap what I had written and focus instead on a single paradox:

Just when we most need the friction that others bring (because it’s in disagreement and the clash of perspectives that we mature and think better!), our relationships have become more controllable than ever.

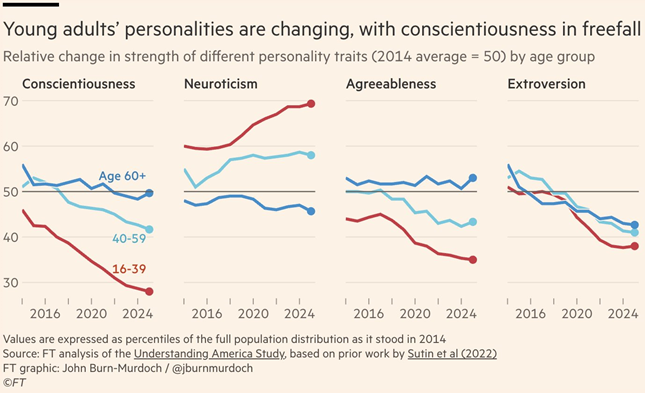

By “controllable,” I mean that we can pause, delete, or mute them with a click. But life doesn’t come with an Esc button. And here’s the paradox: people’s ability to self-regulate (especially the young people) seems to be declining precisely at the moment when technology supposedly gives us more tools to “manage” human relationships.

The Philosophical Problem

This situation, which I think comes at us from many directions at once, makes me think of philosophy’s “problem of the Other.” 1

The complexity of the other is systematically ignored by technical knowledge systems, which emphasize what can be measured and made tangible. But approaching and trying to understand the other is one of humanity’s deepest, most universal challenges.2

What do I mean? The other is a “problem” because it resists being thought as an “I.” Levinas describes the other as infinite, like an asymptote we can never fully reach.3 Understanding other people should occupy a central place in our lives—and if it doesn’t, I believe something might be off.

There are no shortcuts here: we need to spend time with others, get excited about others, and suffer for others.

Some people are especially gifted at understanding the others (which isn’t exactly the same as empathy). And when someone hasn’t done their homework, it often shows up in what we might call a “lack of street-smart.” It’s not a perfect analogy, but it gets at something real.

The Psychological Problem

This philosophical difficulty has very concrete roots. Evolution wired us to analyze others in ways very different from how we analyze ourselves.

And because others are so crucial to our survival, our brains don’t evaluate them neutrally. We label each person based on their relation to us: friend, enemy, stranger, family.4

But this brings us back to our central problem: it’s hard to map out a clear and easy “structure” of possible relationships with others. Learning isn’t linear. You can learn more from a one-month friendship than from a two-year romantic relationship (just to take an extreme case).

And one key point: in general, not feeling means not learning when it comes to the problem of understanding the others.

Even without a clear roadmap, certain personalities and ways of being reward experience with and against others. And that’s where the interferences begin.

The Modern Problem

Today, friction is still seen as an anomaly rather than as a basic condition of life. Everything in the digital world feels tuned to our preferences… except other people.

As a recent example, three different people sent me this paper a few weeks ago:

Without diving into the details, I think it connects directly to what I said earlier about declining self-regulation. Technologies are cannibalizing some of the positive incentives that others provide,⁵ and in doing so, they isolate us.

Of course, it’s normal to withdraw after a breakup, a disappointment, or a sudden decrease in self-esteem. But biology has other plans. The problem is that we are wired to depend on others in ways that go far beyond conscious will.

We are relational beings by evolutionary design: the others are not just “company,” but the mirror we need to exist psychologically.

A silly metaphor: we need others like a phone needs a network. You can put it in airplane mode, but then it stops being a phone.

In this fragile loop between the other and the self (between connection and isolation) we can see the roots of many psychological and social problems. Learning to navigate this loop, I think, will become less common, and therefore more valuable.⁶

And right here, in this space, is where we’re seeing technological substitutes for human relationships appear (a role traditionally occupied by actual humans).

These “relational placebos” may look harmless. After all, if someone is happy with a robot partner or an “AI girlfriend,” what’s the issue?

The same as with a muscle that never gets exercised: it atrophies.

Philosophy gives us clues about the impossibility of fully grasping the other (Levinas). Psychology shows us the mechanisms: labeling, biases, cognitive shortcuts. Technology adds the final trap.

Imagine someone who has only relationships where they can pause whenever things get messy. Paradoxically, to be a functional person we need precisely that controlled dysfunction that comes from dealing with others.

Humanity doesn’t unfold in perfection, it unfolds in friction.

The other is the workout that makes us human.